The moment I stepped into the Forbidden City, the noise of the modern world seemed to fade away.

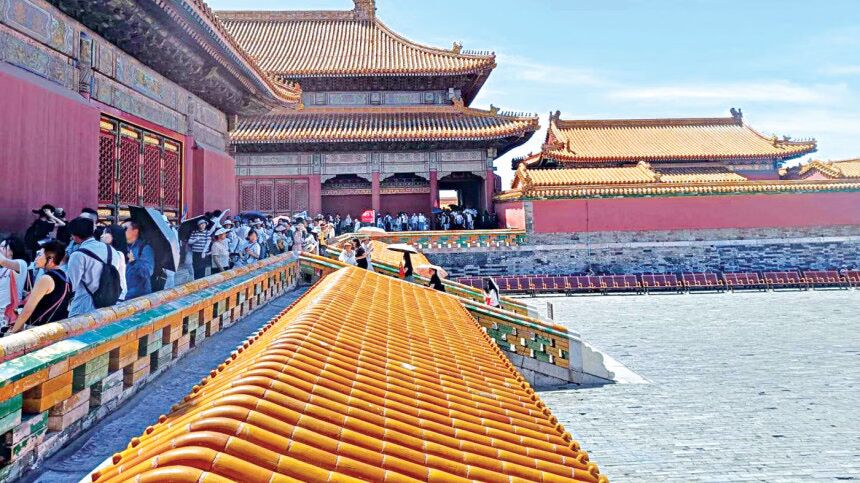

Just moments earlier, Beijing's familiar chaos -- the honking cars, the rush of people, the hum of a vast megacity -- had filled my ears. But as I passed through the towering red gates, everything fell silent. Inside those ancient walls, there was only space and stillness. Standing in a wide courtyard with the sun glinting off golden rooftops, I paused and held my breath. It felt as if I had crossed into another world, a place untouched by time.

I was awestruck by the scale of the compound. The stone-paved courtyard seemed endless, an almost living embodiment of history. I felt small -- a tiny figure within a grand imperial dream. At that moment, I understood why this place was called a city.

The Forbidden City is the largest surviving palace complex on earth, spanning about 720,000 square meters (178 acres) and containing 980 buildings with more than 8,700 rooms. Built by over a million workers in just 14 years, beginning in 1406, it served as the residence of 24 emperors from the Ming and Qing dynasties. Today, it remains the world's most extensive and best-preserved collection of ancient wooden structures.

Not all of its sections are open to visitors. Tourists enter through the southern Meridian Gate and follow a one-way route that leads either to the northern Gate of Divine Prowess or the eastern East Prosperity Gate. Even so, exploring the accessible areas -- the grand ceremonial halls of the Outer Court and the maze-like courtyards of the Inner Court -- can easily take an entire day.

Md Abbas is a journalist at The Daily Star and an avid traveller.

As I began to walk, I was struck by how perfectly everything was arranged. The gates, the halls, the courtyards -- all reflected a deliberate symmetry. Every path seemed to guide me forward, deeper into the city's heart. The sunlight danced on the golden tiles, while the red walls glowed softly. I couldn't stop taking photos, though I knew no image could capture what I was seeing or feeling.

The air itself felt different. It carried a sense of history and quiet mystery, as if the walls were still guarding their secrets. I imagined the emperors who once ruled from these halls, the guards who stood at attention, the servants who hurried silently across the courtyards. The city was now full of tourists, yet I could almost hear the echo of drums, the murmur of courtly rituals, and the faint rustle of silk robes from centuries past.

Eventually, I arrived at one of the grand halls, its stairs flanked by dragons carved in stone. I stopped and tried to picture what it must have been like during an imperial ceremony. I closed my eyes and saw the golden throne at the centre, the emperor seated high above while courtiers bowed before him. When I opened my eyes, the hall was empty -- only visitors with cameras and curious eyes remained.

Everywhere I looked, details captured my attention. The edges of the roofs curved upward like wings, and rows of tiny animal figures stood at the corners, silently watching over the buildings. I had read that these creatures were believed to protect the palace from evil spirits.

As I wandered deeper, my emotions shifted. Sometimes curiosity made me pause to study the intricate door carvings or the painted motifs. Sometimes I felt peace as I walked through wide courtyards bathed in sunlight. And sometimes, an unexpected wave of emotion washed over me -- a realisation that countless lives had passed through this very space, and now I was treading the same stones.

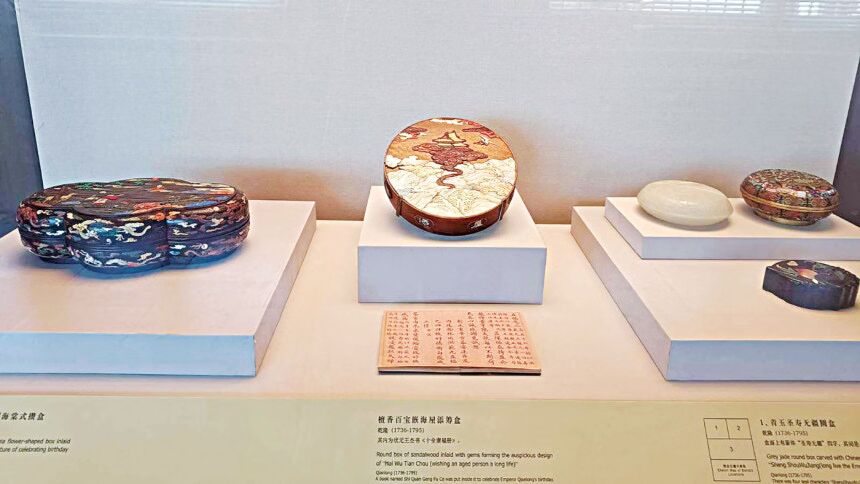

Inside several halls, exhibitions were displayed. Under soft lights, jade carvings glowed like captured moonlight. Porcelain bowls painted with dragons stood beside delicate scrolls of calligraphy. I lingered in front of a yellow silk robe embroidered with dragons and wondered about the emperor who once wore it. These were more than artefacts -- they were fragments of daily life, frozen in time.

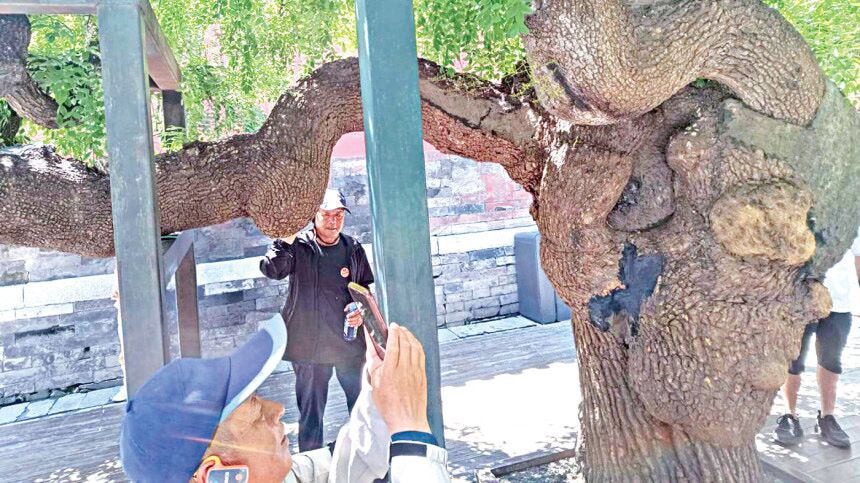

Then I reached my favourite part of the visit: the Imperial Garden. After the grandeur of endless courtyards and massive halls, the garden felt intimate, almost secretive. The air was cooler, scented faintly with cypress. Ancient trees stood tall -- some over 300 years old -- their twisted trunks like living sculptures. I walked slowly among them, resting my hand on the rough bark, imagining how many generations they had silently witnessed.

To my surprise, each tree had a QR code. Scanning one opened a page describing its history and age. I loved this subtle blend of technology and tradition -- standing in a centuries-old garden, using a smartphone to connect with its story. I scanned several more, learning as I went, and each time I felt a little closer to the past.

Eventually, I sat beneath one of the oldest cypress trees and closed my eyes. The sounds of the crowd faded away. For a few moments, I felt perfectly calm, surrounded by whispers of the past. I imagined emperors and empresses strolling through these same paths, seeking a brief moment of peace from the burdens of rule. Perhaps they, too, had sat beneath these trees, listening to birdsong and the rustle of leaves in the wind.

As the day went on, my feelings evolved. At first, there had been excitement and wonder; later, admiration and respect. And toward the end, a soft, reflective sadness. The Forbidden City is now a museum. Its halls are empty, its thrones abandoned, its rooms filled with objects instead of people. The walls that once symbolised absolute power now hold only memories. Yet that sadness wasn't heavy -- it was tender, a quiet acknowledgement that time moves on.

By the time I reached the northern gate, the sun hung low, casting a warm, fading glow over the palace. The red walls deepened to a rich crimson, and the golden roofs shimmered like fire in the dying light. A hush fell over the courtyard as shadows stretched long and soft across the stones. I turned for one last look, and for a fleeting moment, it felt as though the palace itself was breathing -- whispering a slow farewell to the day, and perhaps, to me.

The Forbidden City is no longer forbidden. Stepping beyond the gates, I realised I was leaving with more than memories and photographs. What I carried was something harder to name. Travel, I understood, is not merely about visiting new places. It is about forming a connection -- with the silences, the echoes, and the stories that linger in the stones.

Md Abbas is a journalist at The Daily Star and an avid traveller.